aus: kunst:art Nr. 95, Jänner – Februar 2024 (ISSN 1866-542 X)

Sharks vs. Jets

A fascinating look into the development of Austrian Expressionism can be seen in Vienna right now, in an extensive show that surveys the work of Herbert Boeckl (1894-1966) and Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980). The two artists had a profound impact on the art of the 20th century, in very different ways. This exhibition allows us to compare and contrast their lives and output through an examination of their works on paper. Chief curator of the magnificent graphic collection of Albertina, Dr. Elisabeth Dutz, has selected more than 100 works that allow us to experience the artistic and personal journeys that these two artists made.

The show begins with a look at the work of Oskar Kokoschka before the First World War. Dr. Dutz broaches the idea that Kokoschka is largely the main impetus for the development of early Expressionism in Vienna, and his work made a huge impression on artists such as Egon Schiele. Three emotionally dense drawings of Kokoschka’s lover Alma Mahler, who terminated a pregnancy of his child, capture the eye in the very first room of the show. Their dark and agitated lines seem to express the unhappiness of the love affair. Already in these early works, the inner emotional and psychological state of the person portrayed begins to win the upper hand in the way Kokoschka represents them.

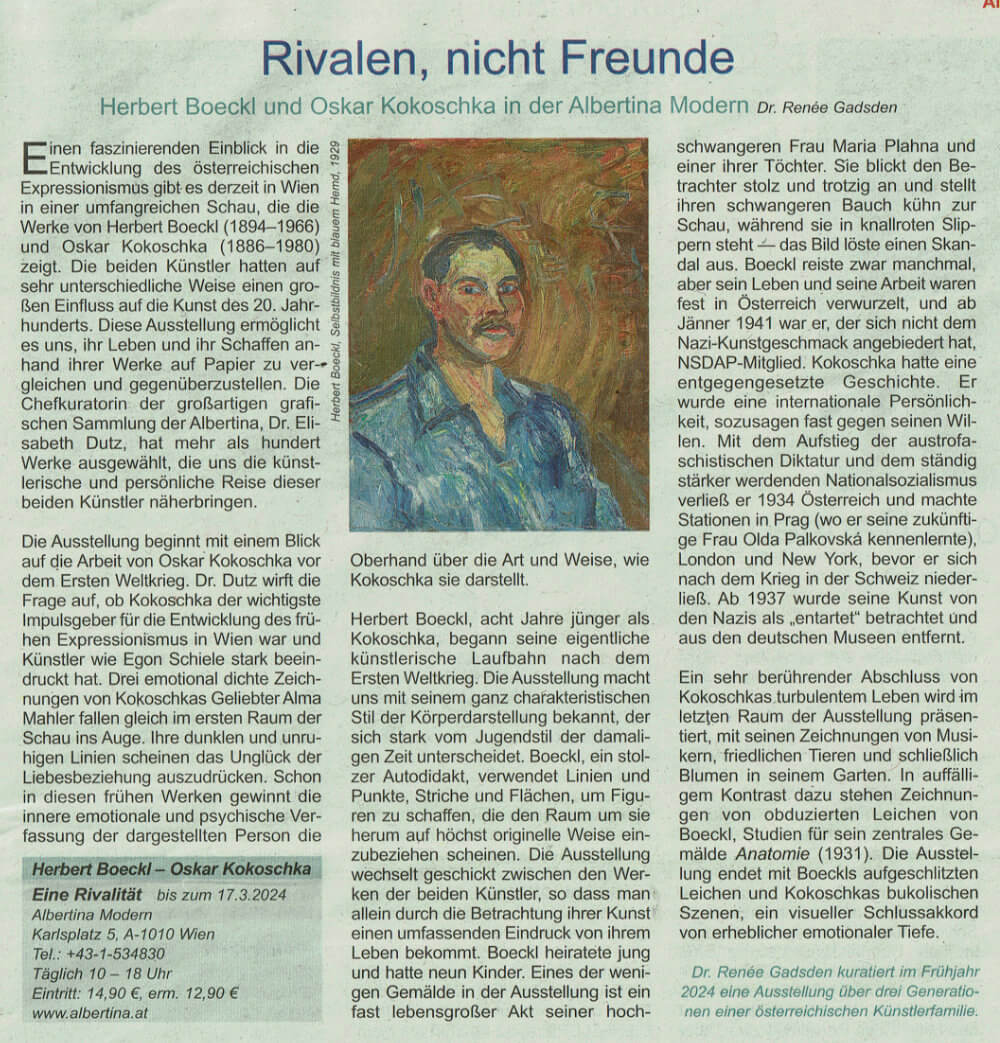

Herbert Boeckl, eight years younger than Kokoschka, began his artistic career after World War I. The show introduces us to his very unique style of rendering bodies, which was very different to the Jugendstil of the time. Boeckl, a proud autodidact, seems to create a space over and above the body he is depicting, using lines and dots, lines and planes to create figures that seem to incorporate the space around them in a most original way. Later, in the 1940s and 1950s, Boeckl attempted to be more abstract, but he stayed close to the figural throughout his oeuvre. In his work as a professor at the Viennese art academy that wouldn’t accept him as a student, Boeckl introduced the “evening nude drawing class” that became a bit of an institution in postwar Austrian art education. For Boeckl, it was paramount that one could draw proportions, and his teaching and ideas directly shaped the talent of a generation of Austrian artists.

The show cleverly alternates between the works of the two artists, so that one gets a deep sense of what their lives were like just by looking at their art. Boeckl married young and had nine children. One of the few paintings in the show is an almost life sized nude of his heavily pregnant wife Maria Plahna and one of their daughters. She looks directly at the viewer in a proud and defiant way, and displays her expectant belly boldly while standing in bright red slip-on shoes — the painting caused a scandal. Boeckl travelled some, but his life and work were firmly rooted in Austria. Kokoschka had an opposite story. He became an international figure, one could say, against his will. He fled Austria in 1934, and made stations in Prague (where he met his future wife Olda Palkovská), London, and New York before settling after the war in Switzerland. His art was considered entartet by the Nazis, removed from German museums.

A very touching denouement to Kokoschka’s turbulent life is presented in the last room of the show, with his drawings of musicians, peaceful animals, and finally, flowers in his garden. In a striking contrast there are drawings of autopsied bodies from Boeckl, studies for his pivotal painting Anatomy (1931). The exhibition ends with Boeckl’s split open corpses, and Kokoschka’s bucolic scenes, a visual final chord of satisfying emotional depth.

Dr. Renée Gadsden